Auke Visser's International Esso Tankers site | home

Esso Rochester Breaks in Half

Source : Report from Quebec Chronicle Saturday December 2nd 1950 on the rescue of Crew.

Standaard;Built in 1943 at the Sun Shipyard Chester, Pennsylvania as Yard No. 213 . She was delivered on 29th January 1943 and had taken 141 days to build. Her sister ships were Esso Richmond, Esso Buffalo and Esso Columbia. All were built for the Panama Transportation Company and under the American flag for war service.

They were of 18604 d.w.t. with a length oa of 547’, bp was 521’; beam was 70’ and the loaded Summer draft 30’4”. Powered by a steam turbine of 9020 shp, steam was from two watertube boilers and speed was 15.5 knots

The Esso Rochester spent over 2 1/2 years in war service in both the Atlantic and Pacific

Following the war the Esso Rochester was re-flagged to Panama and manned and managed by Esso Petroleum Company London.

During a ballast voyage from Montreal to Aruba late afternoon of 30th November 1950 Esso Rochester broke in half in the Gulf of St Lawrence 45.29 N-65.50 W (off Anticosti Island). All except the chief officer, helmsman and lookout were aft in the messroom having their evening meal when the failure occurred.

The forward section was recovered by a tug but sank whilst under tow. The aft section was salvaged and subsequently fitted with rebuilt bow at Newport News in April 1951.

The Esso Rochester remained in service until 1966 when she was scrapped at Onomichi.

A U.S. Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation in 1952 stated these war-built ships were prone to splitting in two in cold weather and they were then "belted" with steel straps or riveted sheer strakes. Two T-2s, SS Pendleton and SS Fort Mercer, had also split in two off Cape Cod within hours of each other. Technical investigations into the problems first suggested the reason for the tankers to split in two was due to poor welding techniques. Later, it was concluded the steel used in the war time construction had a too high sulphur content, and that this turned the steel brittle at lower temperatures. The Esso Rochester was one of the last ships to sail from Montreal before the seasonal closure of the river due to ice.

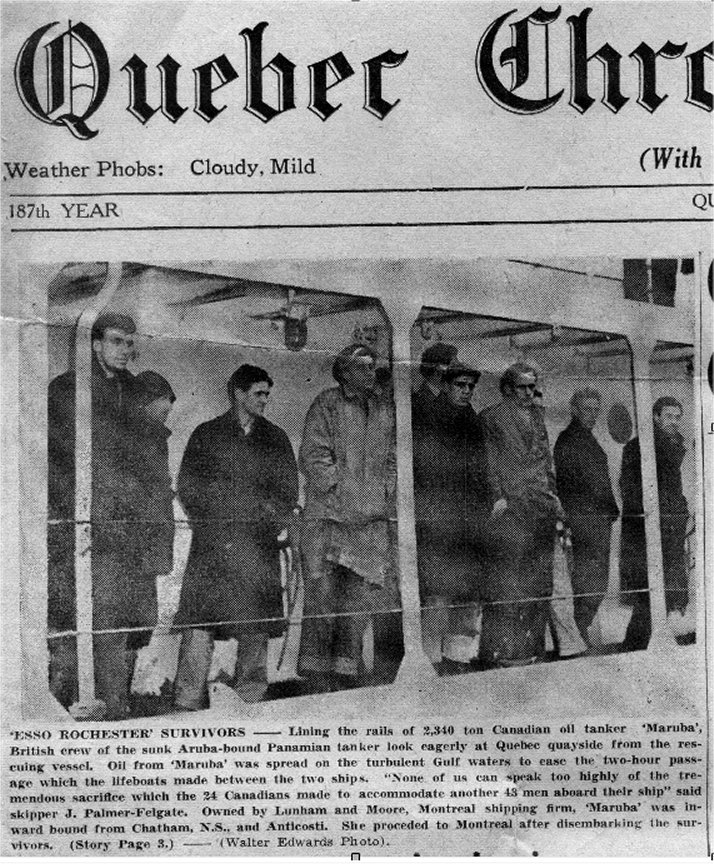

Newspaper article form the Quebec Chronicle Saturday December 2nd.

Newspaper article form the Quebec Chronicle Saturday December 2nd.

The Maruba under Captain J.P. Michaud of Trois Pistoles, Quebec, immediately answered Esso Rochester’s distress signal and reached the stricken vessel about two hours later.

When the Esso Rochester’s decks became awash the order was given by Capt. Palmer-Felgate to Abandon ship. The crew piled into two lifeboats and headed for the Maruba which had been standing by for two hours in heavy seas. One seaman, Michael Pirie of London, was struck in the eye by a pole supporting a lifeboat cover while he attempted to clear the lifeboat. He sported a slightly bruised eye when he arrived in Quebec. The transfer to Maruba was made slightly after midnight Thursday morning. Only accident in the transfer from the Esso Rochester to the Maruba occurred when Thomas Irving, 24, second cook from Newcastle, fell overboard. As he attempted to climb aboard Maruba by ropes, his legs, half frozen from immersion in water in the bottom of the lifeboat, lost their grip and he fell back into the boat.

The second time he attempted to climb he fell overboard and was pulled back on board by some of his shipmates.

The rescue operation was conducted by Boatswain Armaud Samson of Quebec who headed 10 of the Maruba’s 23 crew. The Maruba dumped some 2.000 barrels of oil in the sea in an attempt to calm the heavy seas and circled the stricken ship twice.

Extract from the deposition made by the Master before a Notary Public in New York 4th December 1950

“On October 29 1950 I joined Esso Rochester at Jacksonville, Florida where she had just completed an annual drydocking period. Since then I have made trips from Jacksonville to Aruba, where machinery repairs were effected, from aruba to Amuay Bay where a cargo was loaded and carried to Montreal, Canada, arriving in Montreal on nthe evening of November 24 1950. During my period of command of the vessel I found her to be satisfactory and seaworthy in every way and to handle under all circumstances in a normal fashion.

After discharging at Montreal the vessel received orders to proceed to Aruba with a cargo of fresh water, the orders being to load to winter marks plus allowance for fresh water. Before loading all tanks of the vessel were butterworthed, this operation commencing at approximately 12.30pm November 26 and being completed at approximately 5.30pm November 27th. I wish to state at this time that all times referred to in this affidavit are considered to be my best estimates, inasmuch as no contemporaneous records kept aboard Esso Rochester were saved when the vessl was abandoned. All times given are present recollections, arrived at in reconstructing the succession of events.

After butterworthing was completed, ballasting commenced at approximately 8.00pm on the 27th, with tanks 2 center, 4 center, 6 center and 8 wings being loaded with fresh water at dockside, using three of the vessels pumps. Approximately 7.00am November 28th the vessel sailed from Montreal, and while underway making approximately 70rpm ballasting proceeded with 2 stripper pumps being used to load No.6 tank and the main starboard pump being used to load 3, 5 and 7 center tanks. This was completed during the course of the morning, and the vessel eventually came to anchor at 11.30pm November 28th. While at anchor all vessels pumps were put into operation for the continuous ballasting, at which time 3 wing tank, 8 center and 4 and 5 wing tanks were fully loaded and No. 1 center tank was loaded to the amount of approximately 80 tons for the purpose of setting the vessel at even trim. After ballasting was completed the vessel’s draft was noted at 30 ft. 6inches, all even, and reading is equal to 29ft. 9 inches winter draft, plus 81/4 inches for fresh water, plus ¾ inches for river navigation.

After ballasting was completed vessel hove anchor and proceeded underway at approximately 3.30pm. At approximately 9.15pm November 28th pilots were changed and the vessel proceeded underway without event, eventuall dropped the pilot at Father Point at approximately 7.45am. November 29th. After dropping the pilot the vessel’s speed was gradually increased until she was making 90rpm. Thereafter everything continued aboard without event until approximately 4.05pm., while I was in my room a sea hit her forward. I thereupon called the bridge and ordered speed reduced to 85rpm, the reason being that having had 3 years’ T2 experience I have generally found that reducing 5 revolutions in a seaway assists the vessel to carry on the same speed but with less effect on the vessel. At this time the wind was from the east Force 5, swells were moderate, seas short and vessel shipping spray.

Thereafter the vessel proceeded without incident until at approximately 5.35pm while I was in the messroom aft having tea, I heard a loud crack. I immediately left the messroom and made my way forward to the bridge. While walking forward on the flying bridge (catwalk) I noticed the vessel was riding so low forward so that in walking forward I was walking what may be described as downhill. I would judge the catwalk was 10 to 15 degrees down by the head. During this period of time the alarm bells were rung by the Chief Officer. I made my way to the navigation bridge, where I spoke to the watch officer, who was at a complete loss as to what had happened. I immediately went to the port wing of the bridge. After being there for a few seconds I noticed a large gray painted mass approaching the port wing of the bridge. I did not wait to ascertain what it was; returned to the wheelhouse and ordered everybody aft. I then went to the wireless operator in the radioroom and told Sparks to send an SOS; he replied it was impossible, that the aerials were down. I then ordered him aft as I wished to have everybody aft with me, as the 2 after boats were the only ones we could use. Soon thereafter all hands were mustered aft and the 2 boats swung out on their davits ready for immediate lowering. The radio operator attempted to send an SOS using the lifeboat emergency equipment. We know that an SOS was sent, as to whether it was received we do not know other than we did not receive an acknowledgement.

All hands stood by awaiting developments, and when conditions did not visibly change by approximately 7.10pm the chief mate, chief engineer and myself made our way forward to the bridge to ascertain if possible what had happened, and also to make an attempt on the part of the radio operator to again use the main radio equipment in sending an SOS. Inasmuch as it was dark at the time, all that could be seen was that the vessel had parted forward of the bridge, and no part forward of the bridge could be seen. The mate reported to me that he thought that he saw a movement under the water that looked like the shape of a ship. While forward the radioman kept the original equipment in operation, using the di-pole aerial, and sent another SOS, which was soon acknowledged from the ss ‘Marimba’ of the Ellerman-Wilson Line, who reported that she was approximately 50 miles from our position which was at that time approximately 49.26 North, 65.48 West, or approximately 15 miles north of Riviere a Calude light on the north shore of the Gaspe Peninsula. The ‘Marimba’ relayed this call to Fame Point, who in turn relayed a general alarm to all ships in that area. This alarm was picked up by the mv ‘Maruba’ who informed Fame Point that she was approximately 10 miles from that position. Fame Point then ordered the ‘Maruba’ to come to our assistance and ‘Marimba’ to carry on her passage. At about 6.00pm the vessels engines were put astern at 20 – 25 rpm, this being done to try to relieve the pressure upon the bulkheads as much as possible. In my opinion the operation was successful. Fortunately the wind and sea kept her upright and head into the wind and sea. We continued to stand by and the only apparent visual change being that the vessel was settling further by the head. During this time at intervals we fired distress rockets.

At approximately 8.30 pm the ‘Maruba’ hove in sight on the port bow. We fired our last two rockets. Soon the ‘Maruba’ came alongside within hailing distance and inquired as to our intentions to abandon the vessel. I informed them that we were going to stand by the ship, and asked them to stand by us. They agreed. The ‘Maruba’ then commenced circling ‘Esso Rochester’, discharging oil onto the water which greatly assisted. At approximately 9.30pm. the ‘Maruba called us with his lamp and told me that a tug from Quebec was on its way to our assistance and that the ‘Maruba would stand by us until its arrival, or until the swell stopped.

At 10.30 I noticed that the vessel’s pitching motion was replaced by a gyrating motion. At 10.45 I conferred with the chief officer and chief engineer, and it was agreed that the expedient thing to do now was to abandon the vessel which was completed by 11.10pm, with 22 men including myself in the starboard lifeboat, and the remaining 21 members of the crew in the port lifeboat under the command of the chief officer. I was the last to leave. Both of the boats are oar powered. The vessels engines were stopped before abandoning but all lights were left burning. I noticed that when we left the ship that the aft fling bridge was at an angle of about 35 to 40 degrees, the forward end being the lower. At the time of abandoning ‘Maruba was about 5 miles distant, she steamed towards the two lifeboats. Thereafter the chief officer’s boat was brought alongside ‘Maruba’ at about 12.45 and all occupants boarded her, the boat was cast adrift at about 1.30am. After the chief officer’s boat was cast adrift I brought my boat alongside about 15 minutes later and we all boarded ‘Maruba’; this was accomplished by about 2.00am, at which time my boat was also cast adrift. ‘Maruba’ then proceeded towards Quebec. Whilst on board ‘Maruba’ the chief officer reported that the crew were uninjured except for the 2nd cook who had his leg jammed between the boat and the ship while he was getting aboard. At my request, in a message to Imperial Oil, on arrival in Quebec the whole crew was examined by doctors, all were pronounced fit except the 2nd cook and myself with a minor injury to a finger on my left hand.”

Footnotes;

Captain Palmer-Felgate regretted for many years that he gave the order to abandon Esso Rochester, particularly in view of the fact that the after section remained afloat and was salvaged. At the time of giving the order he believed that the after section would sink. Some years later he sailed with members of the crew who told that they were extremely relieved when the order was given as they had for some time been expecting the ship to sink at any moment.

Although Esso were generally regarded as among the better employers at the time, it was a reflection of how seamen were not highly regarded, that the first question asked of the Captain by the Company was not “how are the crew”, but “Do you have the ships papers and accounts with you”. He apparently replied “Yes, but more importantly I have 43 men with me”. (At the time the ratings contract of employment was with the ship –officers were mainly employed by the Company- all accounts of wages, tax, National Insurance etc were calculated and kept on the ship).

The crew were all repatriated to the UK as DBS (Distressed British Seamen) travelling back on various British vessels. The Captain sailed back in First class accommodation on the ‘Queen Mary’ but regretted that his wardrobe was not up to the normal standard of a First class passenger !

Source : The Lewiston Daily Sun - Dec 2, 1950

ESSO ROCHESTER CREW ARRIVES IN QUEBEC

Ship Wrecked by Hwy Gales; All In Good Condition

QUEBEC, Dec. 1-AP-Tired and bedraggled, 43 crew members of the Esso Rochester, wrecked off Anticosti Island Wednesday night by heavy gales, arrived here today aboard the Montreal-owned tanker Maruba.

The British crew abandoned ship without taking time to save personal possessions. All said they were in "good condition."

Skipper of the wrecked United States Esso Rochester is Captain J. H. Palmer-Falgate of Fresh Water Bay, Isle of Wight.

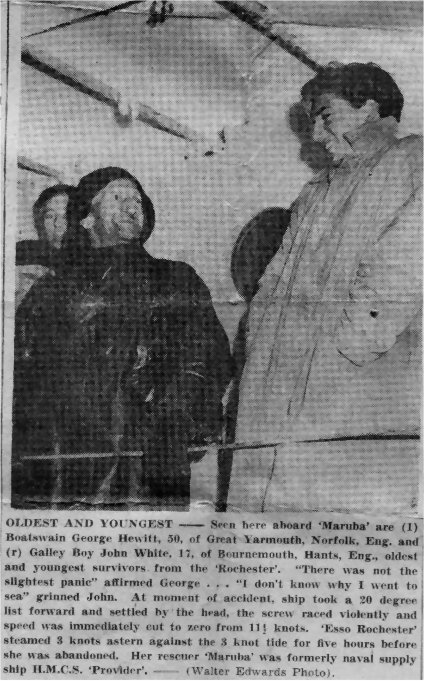

George Hewitt. bosun of the Esso Rochester, 50-year-old veteran of 27 years at sea, described the wrecking of the American ship in a raging gale that sent waves 15 to 20 feet high smashing against the vessel.

He said the ship was finally smashed by two heavy waves from each side.

The crew escaped in two lifeboats.

|