Auke Visser's International Esso Tankers site | home

The Esso Fleet Lay-up site in the 1930s - Part-2

Tankers in the Patuxent: The ESSO Fleet Lay-Up Site in the 1930s

By this time, foreign affiliates had lost eighteen tankers and suffered five more seriously damaged. To maintain a maximum number of ships in operation, ESSO was forced "to carry out extensive repairs to some of our older vessels which, under peace time conditions, would probably have been scrapped.“ The following table, showing growth of the ESSO fleet, is based on data from the company’s annual reports:

ll. THE PATUXENT LAY-UP SITE

ESSO’s major lay-up site was located in the Patuxent, which afforded numerous natural advantages as a long-term mooring point, and had been used by the Shipping Board (and its successor, the Maritime Commission) since 1927. The government leased a strip ashore running eastward from Point Patience, just north of the town of Solomon's. The lease was subsequently included in a Navy Department land acquisition, and is now part of U.S. Naval Recreation Center, Solomon's?“

The Maritime Commission kept a maximum of six ships at Point Patience, but ESSO’s needs were far greater in terms of both physical space and local labor required to work on the idle tankers. The chosen spot was Millstone Landing, a steamboat dock situated roughly between the present east and west seaplane basins of U.S. Naval Air Station, Patuxent, about a mile SSW of Fishing Point and 1.5 miles SSE of Sandy Point (the southern tip of Solomon's Island). The site was just inside the mouth of the Patuxent River, where the river empties into Chesapeake Bay, and provided adequate draft except where shoals ran north from Fishing Point and Hog Point, on the southern shore. Millstone Landing had been a major covert operations center for Confederate smugglers during the Civil War. The land behind the lay-up site was thickly wooded, broken only by a few widely scattered houses, and remained undeveloped until taken by the navy in World War II as an aviation test center. Although isolated, the site was “near Baltimore for repair facilities, ship supplies and convenient for transfer of personnel.“

The number of tankers laid-up at Millstone Landing varied between twenty and forty over the years, in response to fluctuating demands for crude oil, and resultant freight rate changes. Apparently, when more than twenty ships were present, they were divided into two groups, moored about two hundred yards apart.

The tankers were not docked or tied to the shore, but rather placed in the stream and cabled together, "Parallel, side by side, (alternately) bow to stern, anchors ahead, mooring lines as needed.” Deck watchmen were on duty as the officer in charge was “very strict about safety and security" of the vessels."

The lay-up site was organized along the lines of a ship at anchor. The small SS Ethyl had been “stripped to a hull and floating boat house - galley, mess hall, bunks for about 265 men," to serve as “mother ship” of the fleet. The senior unit was the Deck department,

which engaged primarily in such maintenance work as scaling, painting, and rigging. The first department head was a Captain Grunnah, followed by Captains A. C. Steinmuller and (in 1938) Fred Marcus. Next in importance came the Engine Department, led in turn by Emil Cordsen, Edward J. Chadbourne, and Lawrence B. Jones. This unit was occupied "mostly [with] installation of the Butterworth Tank Cleaning System” on ships coming into lay-up. Conversion from crude oil to gasoline carriage required meticulous cleaning of storage tanks. The Butterworth system was a means of “pumping hot salt water under pressure into the tanks to remove deposits.” Standard Oil estimated that the system saved $85,000 on forty-seven major cleaning jobs throughout the fleet during 1931. The last major division was the Steward‘s Department, which was responsible for provisioning, messing and living quarters

for tanker crews. Overall command of the site was vested in a port engineer, a post held first by Guy L. Bennett, then by Chadbourne. This officer reported directly to H. J. Esselbom, manager of the Operations Division at the home office in New York City.“

In its earliest days, the lay-up site employed about one hundred workers. These were mainly fleet crewmen retained as an alternative to layoff, and to provide an element of security. Fleet employees were supplemented by a “crew of shipyard workers from Baltimore to take care of the burning, welding, etc. in the installation of the Butterworth System.” Much of the engine and pump repair work beyond the capability of fleet equipment was trucked to “Buck” Lynch’s machine shop in Baltimore. The small number of “locals” employed at the site increased until they constituted the bulk of a three-to-four-hundred-man workforce in later years.“

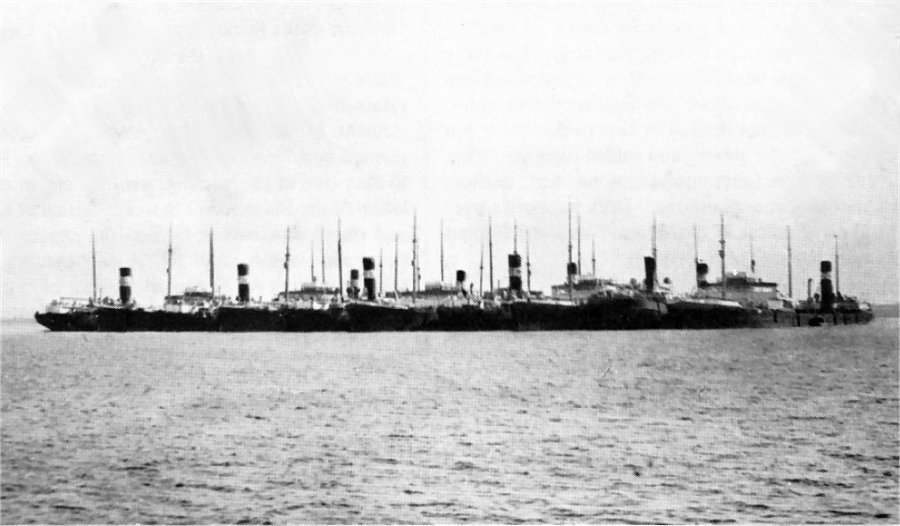

Mothballed ESSO tanker fleet, Patuxent River, Maryland. Group No. 2, 1930-1931, left to right: A. C. Bedford, E. J. Sadler, H. H. Rogers, James McGee, Charles Pratt, Walter Jennings, Wm. G. Warden, Beacon, Beaconlight, and F. Q. Barstow.

(Courtesy of the Calvert Marine Museum, Solomon's, Maryland.)

The locale provided little in the way of recreation.

Other than “bars and a few seafood houses” in Solomon's, fleet employees could find diversion in “movies, slot machines, card games [and] illegal drinking." However, there was “good, daily bus service to Baltimore,” and many employees brought their private automobiles, which permitted travel to Washington and Baltimore in search of amusement."

While shipboard maintenance operations pose a number of occupational hazards, former workers reported no knowledge of workrelated deaths or serious injuries. ESSO kept a company doctor aboard the “mother ship,” and engaged Page C. Jett, a local physician, as medical consultant."

Two natural events came closest to being classifiable as “notable disasters" for the laid-up fleet. A hurricane lashed the Chesapeake Bay region on 22-24 August 1933. This “August storm" caused extensive damage to numerous vessels and marine facilities in the bay and its tributaries. Within the ESSO fleet, men were rousted from bed during the storm to secure tankers with additional cabling, and labored for many hours into the night. Despite their hard work, some ships broke loose and drifted without steam, or food for the skeleton crews, until retrieved. In January-February 1934, an exceptionally cold winter froze the tankers in for several weeks. Indeed, all water traffic was stopped. As Captain Larson observed, “The severe hurricane of 1933 and the solid freeze-up of the harbor the winter of 1934 proved that the fleet was well secured."

One unusual aspect of the Millstone Landing site was its use as a training base for ESSO lifeboat racing crews. In 1927, Capt. John F. Milliken convinced the I985; Smith, Thomas, Larson, and Dingle to author; Taylor interview.

See also Marine Regulations, 60, for duties of a pumpman. In 1940, according to Dingle, each ship was manned by four mates (watchmen) and three engineers. The “mother ship" retained an engine room complement of four engineers and three firemen to keep up steam.

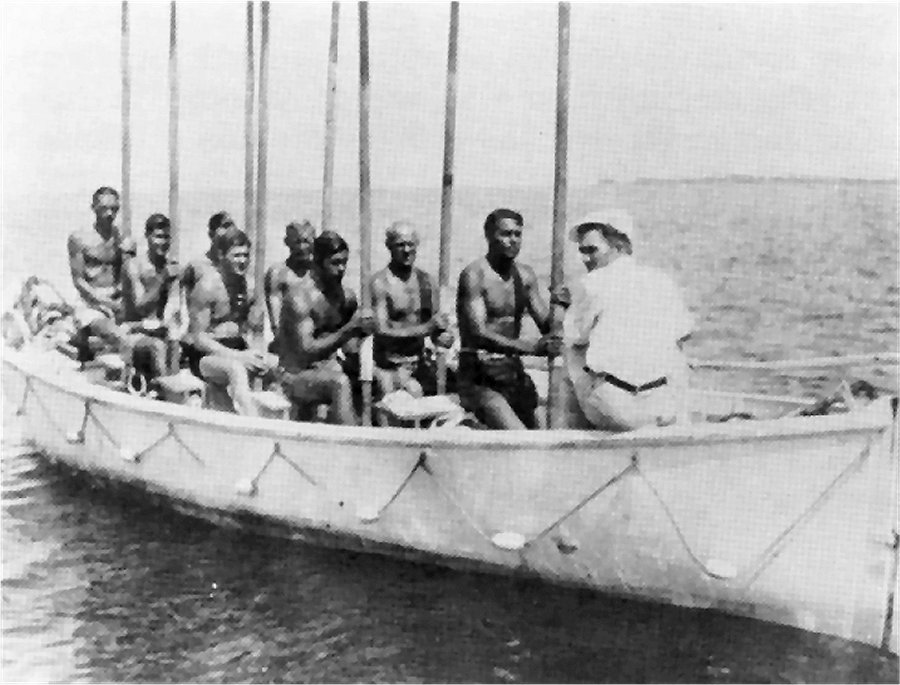

International lifeboat racing team from ESSO tanker C. W. Teagle at Solomon's outer harbor, 1935.

(Courtesy of the Calvert Marine Museum, Solomon's, Maryland.)

Neptune Association to sponsor a lifeboat race to promote international good will. The competition became an annual event and was held each Labor Day in New York Harbor. It involved rowing 2.5-ton lifeboats over a two-mile course from the Narrows to 73d Street. Norwegian crews won every year between 1927 and 1932, except for a British victory in 1928 (no race was held in 1930).

In 1933, Hague offered an impressive silver cup, the R. L. Hague International Lifeboat Racing Trophy, as an additional prize in the competition. This was also the first year that an American crew - from the ESSO fleet - won. This crew lost “the boss’ cup" to the Italians of the Conte di Savoia in 1934, won again in 1935, but lost to the Savoia in 1936 and 1937. The Italians’ third victory retired the Hague cup. There was no race in 1938, and the Teagle team won the last prewar event on Labor Day 1939. ESSO entered crews in postwar competition, but none of these trained in the Patuxent.

Although assigned to the W. C. Teagle, which was not laid up in the Patuxent, the ESSO team was actually housed on the “mother ship” Ethyl. Capt. Adolv Larson was sent to the site in early June 1933 specifically to train the racing crew. One of the original team recalled the selection and training process:

Forty men were picked and were slowly weeded down to eight regular oarsmen, four substitutes and a trainer. On the “Ethyl” we had a chef to cook the food, which was handpicked for athletes in very strict training. Of course we had a galley, comfortable bunks, showers, a sun deck for relaxing.

The rules were strict, no wine, women or song. We trained all summer on the river and in the creeks around Solomon's.

We came ashore and ran up and down the roads for exercise.

Just before Labor Day we went to New York for the race.

During the summers of 1933, 1934, and 1935 we went through the same routine. . . .

In 1937, Mr. Richard Carroll was the trainer and he was killed by a bolt of lightning while the crew was off Sandy Point. . . . [Carroll was split in half by the strike, and two crewmen seated near him were badly burned.]“

The presence of the tankers stirred mixed reactions among the “locals.” As one former employee reported, “Some resented it. Most were glad of the cash money being spent by the men of the ESSO Fleet in a place where there was practically no employment.” Another observed, “There were practically no single girls left in Solomon's. All [were] married to ESSO men." One seasoned ESSO officer paid the “locals” a high compliment. He found them “friendly and cooperative . . . excellent workers - very saw marine men."”

At least one complaint was lodged through official channels. This came from Cary T. Grayson, chairman of the American National Red Cross, in a 2 November 1937 letter to Gen. Julian L. Schley, chief of the Army Corps of Engineers." Grayson complained that

the Standard Oil Company have a bad habit of anchoring a varied number of tank ships in the Patuxent River just south of Solomon‘s Island. . .. The presence of these ships in these waters is a very definite menace to the fishing and oystering. ls it possible to prohibit the semi-permanent mooring of this type of craft in these waters?

Schley’s office forwarded the inquiry to the U.S. Engineer Office in Washington, D.C. on 8 November “for report.” The commander of that unit ordered an investigation and reported back on the 17th. His report is illuminating and worth citation in detail.

1. The Standard Shipping Company of New York . . . has anchored, since about 1930, certain of their laid-up fleet of tankers in Drum Point Harbor, at the mouth of the Patuxent River. The number of vessels in the area has varied but the maximum noted has been twenty-three and they are anchored in compact groups. The area used is along the right bank of the river channel, opposite Solomon's Island, where the minimum channel width is one half mile. The depth of water in the area is 40 to 70 feet. . . .

2. There have not been any complaints received in the interval since 1930 that the vessels obstructed or interfered with navigation or had any adverse effect on fishing or the oyster industry. It is not believed that the anchored vessels can have any effect on oystering since dredging is not permitted by law in the Patuxent River and the depth of water is too great for hand tonging of oysters. Any irreverence [sic] with fishing is not understood as only a small area is occupied by the laid-up fleet. It is known that stringent regulations govern the vessels while anchored in the area, prohibiting the discharge of any oil, debris, etc. overboard.

3. In view of the fact that there is no evidence of any interference with navigation it is not apparent to this office that there is any basis for considering regulations to restrict the use of the area for anchoring of vessels.

General Schley relayed the essence of this report to the complainant on 29 November, apparently closing the issue.

The lay-up site’s declining days are not well documented. An official company history of the fleet’s participation in World War II states that nine tankers were stationed there at various times in 1939, but most apparently had departed by the end of October. The next use of the site came “after the fall of France [May 1940] changed the tanker situation, . . . more than 20 ships [were] tied up in the Patuxent River during the summer and fall of 1940. . . The latest departure date given is June 1941, for Paul H. Harwood, which had been idled since 1 August 1940. Prior to that, the last ships to leave lay-up were Elisha Walker and Dean Emery, both in early November 1940;“

|